An early memory…

I remember sitting at the kitchen table, peering over the rim. I must have been three or four years of age. I sat opposite my mother and sister, spying the coloured pencils scattered over the table and my sister’s exercise book.

I felt the desire to write, to draw like my sister and my arm snaked across the table to grab a pencil. But before I succeeded, my mother’s hand slapped mine away. ‘Wait your turn,’ she said.

I rocked back, blinking.

It was something my mother would often say, or it varied, ‘Your turn will come.’

What was this thing called a ‘turn’?

It wasn’t fair.

I still feel that unfairness to this day. What if my mother had supported my desire to learn? What if she hadn’t cared whether I was going to fit into school or not? As it was, I went to school not knowing my alphabet and ending up in tears for being dumb.

Naturally my sister wasn’t that keen to play with me. While I was busy with dolls and plastic farms and other childish pursuits, my sister had her nose planted in books. When I asked my sister to play with me, she’d say, ‘At the end of the chapter.’

Despite all the pages turned, the end of the chapter never came.

When my sister was given a brand-new purple typewriter, I wanted to play with it, but that meant entering my sister’s bedroom uninvited. Of course, that didn’t make me popular. ‘Marm,’ my sister yelled whenever I was caught pressing those wondrous typewriter keys, ‘Lizzy’s in my bedroom again.’

Our mother yelled from the kitchen, ‘Get out.’

Pleas for my own typewriter came to naught. Life was so unfair.

My sister had an imaginary friend when she was a child but then, as a teenager, she had real friends. Of course, I wanted to play with her friends but having a pesky younger sister around wasn’t her vibe. I stood in the doorway watching them sitting in a circle. One friend played a guitar and someone else sang.

Our mother sidled up to me. She said, ‘They don’t like children so stay away.’ I slunk into my bedroom and sulked.

My sister could sometimes be a little mean. One day I thought she was about to include me in a game with her friends. She said, ‘Count to one hundred and then come find us.’

Thrilled, I stood in a corner, outside the house, eyes closed, counting, listening, and counting as a gully wind whisked my hair into rattails. I searched the backyard, the dusty shed full of our father’s gardening tools, the rumpus room where our mother stored rolls of sewing fabric and a buckled table tennis table. I’d all but given up when my sister et al returned from the local deli licking ice creams and laughing.

My sister played the piano but after about four years gave up. Her playing was deemed irrevocably mechanical. Apparently, it was impossible to teach musicality. I saw an opportunity to become the musician of the family.

Fearlessly, my sister launched herself at the world. She was popular, sporty, extroverted, magnetic, the leader of the local Youth Group, run by the church. She was smart, especially at maths, taking after her grandfathers. One grandfather had been a human calculator, employed as a clerk at the Australian Wheat Board. He was as fast as the comptometers – a key-driven mechanical calculator, the first one to gain commercial success, invented in 1862, it could perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. The comptometrists would give him pages of numbers to check their work. He would run his finger along the columns and, at lightning speed, locate an error. On weekends, our other grandfather had a part-time job as a bookmaker’s assistant at the horse races. He never needed to write anything down. He kept all the numbers in his head, the odds, the punters’ bets, the winners’ dues. Such was my sister’s genetic inheritance, her golden ticket to recognition, approval, belonging. Her future was bright. Then there was me whom the genetic lottery had not favoured. I struggled with decimal points. My blotchy future was a continuation of the soggy present. Hazy.

Doctors discovered that my sister was lactose intolerant and keeping milk out of her diet improved her health. I continued to drink milk. My sister suffered asthma attacks and bouts of hay fever, but not as frequently as me. Sometimes we were home at the same time, keeping our mother busy as she oscillated from one bedroom to the other, tending to her ‘sick little chicks’, as she called us. My sister was always faster to return to school.

When she was fourteen, my sister had an operation to expose the eye teeth buried in the roof of her mouth. Her anaesthetist saved her life. He recognised that her body was not metabolising the anaesthetic – scoline – and feared a rare anaphylaxis reaction. If he had not stopped administrating it, her lungs and heart would have become paralysed, and she would have died. Fortunately, he knew the signs and stopped, careful that she did not wake up during the operation. Afterwards, a test showed that she was missing an enzyme – a genetic abnormality. The anaesthetic may as well have been poison.

The thought of my sister dying was inconceivable. I worried about something terrible happening to her for weeks, months, years. My sister wore braces to move her eye teeth into their correct position. Once there, no-one would suspect what those teeth could have cost her.

My sister started kissing boys on the ugly brown lounge in the semi-darkened living room when they were supposed to be watching TV. Our mother and father were oblivious to my sister’s behaviour, washing dishes, deep in discussion, behind closed doors. I thought about alerting our parents, but I was too fascinated by the kissing to do anything but spy.

My sister went on diets. The bickie barrel was emptied in the kitchen cupboard to avoid temptation. Packets of chips were banned. Our mother stopped baking sponge cakes and dipping them in chocolate sauce and desiccated coconut to make my favourite lamingtons. My sister wore blue eye shadow and curled her eye lashes with tongs. At the age of sixteen, she won Miss Beauty Most Improved 1976 at Charm School. Two men in suits and a woman in a fancy silver dress – revealing more cleavage than I had ever seen in my life – had judged the competition. My sister wore a crown which impressed me no end. My sister was a princess. First prize was an eight-hour bus trip to Melbourne and a three-night stay at The Koala Inn. The family went to the ‘Big Smoke’ – the farthest I had ever travelled in my life – and the golden aura of success made my sister invincible, at least in my eyes.

When my sister turned seventeen, war broke out when she started dating Malcolm the Schweppes Sales Rep. He drove a dark blue Chrysler Valiant Charger. Our mother said Malcolm was ‘short on prospects and short on planks.’

My sister shrugged her shoulders and jumped into Malcolm’s car most nights, neglecting her homework.

‘He’s going to ruin your life,’ our mother said, time and time again, to no avail.

A lot of yelling ensued, night after night. Doors slammed. More yelling. More slamming. The verbal brawl lasted days, weeks, months. Our mother pleaded with our father to ‘say something’ but he shrugged his shoulders and shook his head.

Our mother continued to storm. No, she embodied the storm. ‘I’m going greyer by the day,’ she said, wringing her hands instead of wringing her daughter’s neck. ‘How can I make her see sense?’

I hid in my bedroom, pulling the blankets over my head.

Months of conflict later, I went with my sister and Malcolm to a trade fair. I had no interest in the information stands, the demonstrations, the crowd pressing around me, the plastic cups filled with soft drink samples, the pretty women selling raffle tickets, or in Malcolm. All I could think about was dragging my sister away from him and making an escape. I would force my sister to finally see reason. I spent the entire time clutching my sister’s hands, pulling on her arms, but my sister was stronger. She said she regretted taking me to the fair.

Back home, when my sister relayed what had happened that afternoon, our mother sighed and said, ‘What is wrong with that girl?’

I crept back to my bedroom, knowing the situation was hopeless. Why had I thought I could change my sister’s mind? Even our mother had failed, for all her towering rage. It was David against Goliath.

A few weeks later, our mother announced that she wanted to meet Malcolm. She wanted to ‘have a word’ with him. Perhaps my sister believed that once Malcolm was ‘met’ the war would end. Or perhaps my sister thought that pitching Malcolm against our mother would be interesting. Perhaps her relationship with Malcolm needed an injection of excitement. Whatever the case, my sister agreed, and the showdown was scheduled. I hardly slept.

Sunday afternoon, my sister opened the front door and Malcolm entered the house. An eerie calm descended, as if it was the eye of the storm. Our mother smiled with award winning sincerity. Our father shook Malcolm’s hand. Using her nicest voice – her telephone voice – our mother invited Malcolm to sit in the living room and asked if he wanted a drink.

Malcolm sat on the ugly brown lounge next to my sister and held her hand. His mullet and moustache neat and tidy. His square jaw set.

Our mother asked Malcom about his job, his parents, his schooling. It was as if nothing was wrong with Malcolm, as if the months and months of mother-daughter fighting hadn’t happened. Our mother’s deception fried the circuitry in my twelve-year-old brain because Malcolm was the enemy, and he wasn’t welcome in this house.

I tasted something bitter. My vision pixilated. Heat flooded my face and neck. Months of pent-up emotion clogged my throat and exited my mouth all at once. A high-pitched keening, an indecipherable distress signal, filled the living room.

As eyes bore into me, a stifling weight pressed my chest. I was in a rocket making its ascent against the pull of gravity. The room spun.

Through clenched teeth our mother said, ‘Stop your fussing.’ But I found myself incapable of stopping, which multiplied my anguish. My arms flailed, sending crazy semaphore signals without the hand-held flags. I gasped for air and sank into the cushions of the armchair. I was about to crumble to the floor when our mother said, ‘Phil, do something, for God’s sake. Take your daughter away.’

Our father sprang to his feet. He collected me under one arm, led me out of the room and into the laundry where my hysteria continued. Our father shut the door and slapped me on the bottom for the first time in my life. The shock of it stopped me mid-wail. I swooned onto the lid of the washing machine instead of folding to the floor.

‘Do what your mother says,’ our father said, leaving me alone to shake and blubber.

Malcolm must have left. The incident was best forgotten.

The next day our mother asked, ‘Are you over your silly turn?’

I felt as if a bus had run over me and left me mangled by the side of the road.

Then, surprisingly, Malcolm left for good, and my sister cried. Perhaps our mother’s strategy had worked. Her smile was jubilant.

My sister recovered and regained her natural buoyancy. Neither our mother nor my sister uttered Malcolm’s name again. The house settled on its foundations. I tiptoed on eggshells. I didn’t trust the peace treaty.

I’ll leave this story there for now and perhaps return to it next time.

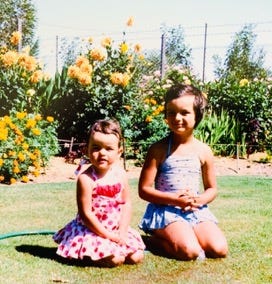

Sibling relationships can be complex, intense, dynamic, competitive and not very close. My sister and I never did sisterly things together: swap clothes, share make up tips or do each other’s hair. We never shared any physical affection, although we were often photographed holding each other’s hand or sitting quite close together. That was encouraged for photographs. For the most part, we grew up independently of each other. We played a lot of card games as a family and that may have been neutral ground, so to speak. I looked up to my sister and loved her even if love may not have been mutual at times. We were different individuals, with different trajectories, and different objectives in life.

Thank you for reading this blog and for being here. It means the world.

With love,

Lil X

PS If you have siblings, how has your relationship been? Do you think giftedness has impacted the dynamics between you? Do you think birth order plays a part? Have you been close or remote in some way? Has the dynamics enhanced your life or hindered it? In an ideal world, what would your relationship with your sibling(s) be like?

Share this post